|

Big Wind

Where were the greenhouses going,

Lunging into the lashing

Wind driving water

So far down the river

All the faucets stopped?—

So we drained the manure-machine

For the steam plant,

Pumping the stale mixture

Into the rusty boilers,

Watching the pressure gauge

Waver over to red,

As the seams hissed

And the live steam

Drove to the far

End of the rose-house,

Where the worst wind was,

Creaking the cypress window-frames,

Cracking so much thin glass

We stayed all night,

Stuffing the holes with burlap;

But she rode it out,

That old rose-house,

She hove into the teeth of it,

The core and pith of that ugly storm,

Ploughing with her stiff prow,

Bucking into the wind-waves

That broke over the whole of her,

Flailing her sides with spray,

Flinging long strings of wet across the roof-top,

Finally veering, wearing themselves out, merely

Whistling thinly under the wind-vents;

She sailed until the calm morning,

Carrying her full cargo of roses.

Child on Top of the Greenhouse

The wind billowing out the seat of my britches,

My feet crackling splinters of glass and dried putty,

The half-grown chrysanthemums staring up like accusers,

Up through the streaked glass, flashing with sunlight,

A few white clouds all rushing eastward,

A line of elms plunging and tossing like horses,

And

everyone, everyone pointing up and shouting!

This urge, wrestle, resurrection of dry sticks,

Cut stems struggling to put down feet,

What saint strained so much,

Rose on such lopped limbs to a new life?

I can hear, underground, that sucking and sobbing,

In my veins, in my bones I feel it,—

The small waters seeping upward,

The tight grains parting at last.

When sprouts break out,

Slippery as fish,

I

quail, lean to beginnings, sheath-wet.

Elegy for Jane

I remember the neckcurls, limp and damp as tendrils;

And her quick look, a sidelong pickerel smile;

And how, once startled into talk, the light syllables leaped

for her,

And she balanced in the delight of her thought,

A wren, happy, tail into the wind,

Her song trembling the twigs and small branches.

The shade sang with her;

The leaves, their whispers turned to kissing;

And the mold sang in the bleached valleys under the rose.

Oh, when she was sad, she cast herself down into such a pure

depth,

Even a father could not find her:

Scraping her cheek against straw;

Stirring the clearest water.

My sparrow, you are not here,

Waiting like a fern, making a spiny shadow.

The sides of wet stones cannot console me,

Nor the moss, wound with the last light.

If only I could nudge you from this sleep,

My maimed darling, my skittery pigeon.

Over this damp grave I speak the words of my love:

I, with no rights in this matter,

Neither

father nor lover.

I Knew a Woman

I knew a woman, lovely in her bones,

When small birds sighed, she would sigh back at them;

Ah, when she moved, she moved more ways than one:

The shapes a bright container can contain!

Of her choice virtues only gods should speak,

Or English poets who grew up on Greek

(I’d have them sing in chorus, cheek to cheek).

How well her wishes went! She stroked my chin,

She taught me Turn, and Counter-turn, and Stand;

She taught me Touch, that undulant white skin;

I nibbled meekly from her proffered hand;

She was the sickle; I, poor I, the rake,

Coming behind her for her pretty sake

(But what prodigious mowing we did make).

Love likes a gander, and adores a goose:

Her full lips pursed, the errant note to seize;

She played it quick, she played it light and loose;

My eyes, they dazzled at her flowing knees;

Her several parts could keep a pure repose,

Or one hip quiver with a mobile nose

(She moved in circles, and those circles moved).

Let seed be grass, and grass turn into hay:

I’m martyr to a motion not my own;

What’s freedom for? To know eternity.

I swear she cast a shadow white as stone.

But who would count eternity in days?

These old bones live to learn her wanton ways:

(I

measure time by how a body sways).

In a Dark Time

In a dark time, the eye begins to see,

I meet my shadow in the deepening shade;

I hear my echo in the echoing wood—

A lord of nature weeping to a tree.

I live between the heron and the wren,

Beasts of the hill and serpents of the den.

What’s madness but nobility of soul

At odds with circumstance? The day’s on fire!

I know the purity of pure despair,

My shadow pinned against a sweating wall.

That place among the rocks—is it a cave,

Or winding path? The edge is what I have.

A steady storm of correspondences!

A night flowing with birds, a ragged moon,

And in broad day the midnight come again!

A man goes far to find out what he is—

Death of the self in a long, tearless night,

All natural shapes blazing unnatural light.

Dark, dark my light, and darker my desire.

My soul, like some heat-maddened summer fly,

Keeps buzzing at the sill. Which I is I?

A fallen man, I climb out of my fear.

The mind enters itself, and God the mind,

And

one is One, free in the tearing wind.

In purest song one plays the constant fool

As changes shimmer in the inner eye.

I stare and stare into a deepening pool

And tell myself my image cannot die.

I love myself: that’s my one constancy.

Oh, to be something else, yet still to be!

Sweet Christ, rejoice in my infirmity;

There’s little left I care to call my own.

Today they drained the fluid from a knee

And pumped a shoulder full of cortisone;

Thus I conform to my divinity

By dying inward, like an aging tree.

The instant ages on the living eye;

Light on its rounds, a pure extreme of light

Breaks on me as my meager flesh breaks down—

The soul delights in that extremity.

Blessed the meek; they shall inherit wrath;

I’m son and father of my only death.

A mind too active is no mind at all;

The deep eye sees the shimmer on the stone;

The eternal seeks, and finds, the temporal,

The change from dark to light of the slow moon,

Dead to myself, and all I hold most dear,

I move beyond the reach of wind and fire.

Deep in the greens of summer sing the lives

I’ve come to love. A vireo whets its bill.

The great day balances upon the leaves;

My ears still hear the bird when all is still;

My soul is still my soul, and still the Son,

And knowing this, I am not yet undone.

Things without hands take hands: there is no choice,—

Eternity’s not easily come by.

When opposites come suddenly in place,

I teach my eyes to hear, my ears to see

How body from spirit slowly does unwind

Until we are pure spirit at the end.

My Papa’s

Waltz

The whiskey on your breath

Could make a small boy dizzy;

But I hung on like death:

Such waltzing was not easy.

We romped until the pans

Slid from the kitchen shelf;

My mother’s countenance

Could not unfrown itself.

The hand that held my wrist

Was battered on one knuckle;

At every step you missed

My right ear scraped a buckle.

You beat time on my head

With a palm caked hard by dirt,

Then waltzed me off to bed

Still

clinging to your shirt.

Open House

My secrets cry aloud.

I have no need for tongue.

My heart keeps open house,

My doors are widely swung.

An epic of the eyes

My love, with no disguise.

My truths are all foreknown,

This anguish self-revealed.

I’m naked to the bone,

With nakedness my shield.

Myself is what I wear:

I keep the spirit spare.

The anger will endure,

The deed will speak the truth

In language strict and pure.

I stop the lying mouth:

Rage warps my clearest cry

To

witless agony.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Root Cellar

Nothing would sleep in that cellar, dank as a ditch,

Bulbs broke out of boxes hunting for chinks in the dark,

Shoots dangled and drooped,

Lolling obscenely from mildewed crates,

Hung down long yellow evil necks, like tropical snakes.

And what a congress of stinks!—

Roots ripe as old bait,

Pulpy stems, rank, silo-rich,

Leaf-mold, manure, lime, piled against slippery planks.

Nothing would give up life:

Even

the dirt kept breathing a small breath.

The Bat

By day the bat is cousin to the mouse. He likes

the attic of an ageing house.

His fingers make a hat about his head.

His pulse beat is so slow we think him dead.

He loops in crazy figures half the night

Among the trees that face the corner light.

But when he brushes up against a screen,

We are afraid of what our eyes have seen:

For something is amiss or out of place

When

mice with wings can wear a human face.

The Geranium

When I put her out, once, by the garbage pail,

She looked so limp and bedraggled,

So foolish and trusting, like a sick poodle,

Or a wizened aster in late September,

I brought her back in again

For a new routine—

Vitamins, water, and whatever

Sustenance seemed sensible

At the time: she’d lived

So long on gin, bobbie pins, half-smoked cigars, dead beer,

Her shriveled petals falling

On the faded carpet, the stale

Steak grease stuck to her fuzzy leaves.

(Dried-out, she creaked like a tulip.)

The things she endured!—

The dumb dames shrieking half the night

Or the two of us, alone, both seedy,

Me breathing booze at her,

She leaning out of her pot toward the window.

Near the end, she seemed almost to hear me—

And that was scary—

So when that snuffling cretin of a maid

Threw her, pot and all, into the trash-can,

I said nothing.

But I sacked the presumptuous hag the next week,

I was

that lonely

The Meadow Mouse

1

In a shoe box stuffed in an old nylon stocking

Sleeps the baby mouse I found in the meadow,

Where he trembled and shook beneath a stick

Till I caught him up by the tail and brought him in,

Cradled in my hand,

A little quaker, the whole body of him trembling,

His absurd whiskers sticking out like a cartoon-mouse,

His feet like small leaves,

Little lizard-feet,

Whitish and spread wide when he tried to struggle away,

Wriggling like a miniscule puppy.

Now he’s eaten his three kinds of cheese and drunk from his

bottle-cap watering-trough—

So much he just lies in one corner,

His tail curled under him, his belly big

As his head; his bat-like ears

Twitching, tilting toward the least sound.

Do I imagine he no longer trembles

When I come close to him?

He seems no longer to tremble.

2

But this morning the shoe-box house on the back porch is

empty.

Where has he gone, my meadow mouse,

My thumb of a child that nuzzled in my palm?—

To run under the hawk’s wing,

Under the eye of the great owl watching from the elm-tree,

To live by courtesy of the shrike, the snake, the tom-cat.

I think of the nestling fallen into the deep grass,

The turtle gasping in the dusty rubble of the highway,

The paralytic stunned in the tub, and the water rising,—

All

things innocent, hapless, forsaken.

The Minimal

I study the lives on a leaf: the little

Sleepers, numb nudgers in cold dimensions,

Beetles in caves, newts, stone-deaf fishes,

Lice tethered to long limp subterranean weeds,

Squirmers in bogs,

And bacterial creepers

Wriggling through wounds

Like elvers in ponds,

Their wan mouths kissing the warm sutures,

Cleaning and caressing,

Creeping

and healing.

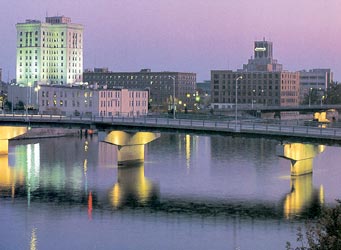

The Saginaw Song

In Saginaw, in Saginaw,

The wind

blows up your feet,

When the ladies’ guild puts on a feed,

There’s

beans on every plate,

And if you eat more than you should,

Destruction is complete.

Out Hemlock Way there is a stream

That

some have called Swan Creek;

The turtles have bloodsucker sores,

And

mossy filthy feet;

The bottoms of migrating ducks

Come off

it much less neat.

In Saginaw, in Saginaw,

Bartenders think no ill;

But they’ve ways of indicating when

You are

not acting well:

They throw you through the front plate glass

And then

send you the bill.

The Morleys and the Burrows are

The

aristocracy;

A likely thing for they’re no worse

Than the

likes of you or me,—

A picture window’s one you can’t

Raise up

when you would pee.

In Shaginaw, in Shaginaw

I went

to Shunday Shule;

The only thing I ever learned

Was

called the Golden Rhule,—

But that’s enough for any man

What’s

not a proper fool.

I took the pledge cards on my bike;

I helped

out with the books;

The stingy members when they signed

Made

with their stingy looks,—

The largest contributions came

From the

town’s biggest crooks.

In Saginaw, in Saginaw,

There’s

never a household fart,

For if it did occur,

It would

blow the place apart,—

I met a woman who could break wind

And she

is my sweet-heart.

O, I’m the genius of the world,—

Of that

you can be sure,

But alas, alack, and me achin’ back,

I’m

often a drunken boor;

But when I die—and that won’t be soon—

I’ll

sing with dear Tom Moore,

With

that lovely man, Tom Moore.

Coda:

My father never used a stick,

He

slapped me with his hand;

He was a Prussian through and through

And knew

how to command;

I ran behind him every day

He

walked our greenhouse land.

I saw a figure in a cloud, A child

upon her breast,

And it was O, my mother O, And she

was half-undressed,

All women, O, are beautiful

When

they are half-undressed.

The Sloth

In moving-slow he has no Peer.

You ask him something in his ear;

He thinks about it for a Year;

And, then, before he says a Word

There, upside down (unlike a Bird)

He will assume that you have Heard—

A most Ex-as-per-at-ing Lug.

But should you call his manner Smug,

He'll sigh and give his Branch a Hug;

Then off again to Sleep he goes,

Still swaying gently by his Toes,

And

you just know he knows he knows.

The Visitant

1

A cloud moved close. The bulk of the wind shifted.

A tree swayed over water.

A voice said:

Stay. Stay by the slip-ooze. Stay.

Dearest tree, I said, may I rest here?

A ripple made a soft reply.

I waited, alert as a dog.

The leech clinging to a stone waited;

And the crab, the quiet breather.

2

Slow, slow as a fish she came,

Slow as a fish coming forward,

Swaying in a long wave;

Her skirts not touching a leaf,

Her white arms reaching towards me.

She came without sound,

Without brushing the wet stones,

In the soft dark of early evening,

She came,

The wind in her hair,

The moon beginning.

3

I woke in the first of morning.

Staring at a tree, I felt the pulse of a stone.

Where’s she now, I kept saying.

Where’s she now, the mountain’s downy girl?

But the bright day had no answer.

A wind stirred in a web of appleworms;

The

tree, the close willow, swayed.

The Waking

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

I feel my fate in what I cannot fear.

I learn by going where I have to go.

We think by feeling. What is there to know?

I hear my being dance from ear to ear.

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

Of those so close beside me, which are you?

God bless the Ground! I shall walk softly there,

And learn by going where I have to go.

Light takes the Tree; but who can tell us how?

The lowly worm climbs up a winding stair;

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

Great Nature has another thing to do

To you and me; so take the lively air,

And, lovely, learn by going where to go.

This shaking keeps me steady. I should know.

What falls away is always. And is near.

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

I

learn by going where I have to go.

|

|

|

|

|